Abstract

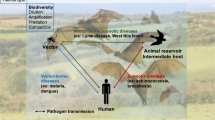

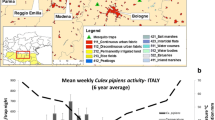

The emergence of West Nile Virus, as well as other emerging diseases, is linked to complex ecosystem processes such as climate change and constitutes an important threat to population health. Traditional public health intervention activities related to vector surveillance and control tend to be reactive and limited in their ability to deal with multiple epidemics and in their consideration of population health determinants. This paper reviews the current status of West Nile Virus in Canada and describes how complex systems and geographical perspectives help to acknowledge the influence of ecosystem processes on population health. It also provides examples of how these perspectives can be integrated into population-based intervention strategies.

Réumé

L’apparition du virus du Nil occidental, à l’instar d’autres maladies émergentes, résulte de processus écosystémiques complexes, comme le changement climatique, et représente une importante menace pour la santé. Les interventions traditionnelles de santé publique, telles que la surveillance et le contrôle des vecteurs, demeurent limitées dans leur capacité d’endiguer les épidémies ou d’agir sur leurs déterminants. Cet article examine la situation canadienne et l’état actuel des connaissances sur le virus du Nil occidental. En s’appuyant sur une analyse des systèmes complexes et une analyse spatiale, il décrit comment les écosystèmes influencent la santé des populations et, en conséquence, quelles stratégies d’intervention populationnelle pourraient être envisagées.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lederberg J, Shope RE, Oaks SC (Eds.) Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1992.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Preventing Emerging Infectious Diseases: A Strategy for the Twenty-first Century. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 1998.

Charron DF. Potential impacts of global warming and climate change on the epidemiology of zoonotic diseases in Canada. Can J Public Health 2002;93(5):334–35.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). The Resistance Phenomenon in Microbes and Infectious Disease Vectors: Implications for Human Health and Strategies for Containment. In: Knobler SL, Lemon SM, Najafi M, Burroughs T (Eds.), Forum on Emerging Infections, Board on Global Health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2003.

Elias SA. Insects and climate change: Fossil evidence from the Rocky Mountains. Bioscience 1995;41(8):552–59.

Morse SS. Emerging viruses: Defining the rules for viral traffic. Perspect Biol Med 1991;34(3):387–409.

Levins R, Awerbuch T, Brinkmann U. The emergence of new diseases. Am Sci 1994;82:59–60.

Epstein PR. Emerging diseases and ecosystem instability: New threats to public health. Am J Public Health 1995;85(2):168–72.

Calisher CH. West Nile Virus in the new world: Appearance, persistence, and adaptation to new econiche — an opportunity taken. Viral Immunol 2000;13:411–14.

Campbell GL, Marfin AA, Lanciotti RS, Gubler DJ. West Nile Virus. Lancet: Infect Dis 2002;2:519–29.

Craven RB, Roehrig JT. West Nile Virus. JAMA 2001;286:651–53.

Centers for Disease Control. Epidemic/Epizootic West Nile Virus in the United States: Revised Guidelines for Surveillance, Prevention, and Control. Workshop on health in Charlotte, North Carolina. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2001.

Nash D, Mostashari F, Fine A, Miller J, O’Leary D, Murray K, et al. The outbreak of West Nile Virus infection in the New York City area in 1999. N Engl J Med 2001;344(24):1807–14.

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHTLC). West Nile Virus Preparedness and Prevention Plan for Ontario, 2003. Toronto, ON: MOHTLC, 2003.

Environmental Risk Analysis Program. What’s going on with West Nile Virus? Cornell University, Center for the Environment. September 17, 2003. Available at https://doi.org/www.environmentalrisk.cornell.edu/WNV/. Accessed February 2004.

Centers for Disease Control. Update: Investigations of West Nile Virus infections in recipients of organ transplantation and blood transfusion. MMWR 2002;51(39):879.

Centers for Disease Control. Possible West Nile Virus transmission to an infant through breast feeding. MMWR 2002;51(39):877–78.

Centers for Disease Control. Provisional surveillance summary of the West Nile Virus epidemic — United States, January-November 2002. MMWR 2002;51:1129–33.

Levin SA. Ecosystems and the biosphere as complex adaptive systems. Ecosystems 1998;1:431–36.

Ewald PW. Evolution of Infectious Disease. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Wilson ML. Ecology and infectious disease. In: Aron JL, Patz J (Eds), Ecosystem Change and Public Health: A Global Perspective. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001;283–324.

Hartvigsen G, Kinzing A, Peterson G. Use and analysis of complex adaptive systems in ecosystem science: Overview of special section. Ecosystems 1998;1:427–30.

Jansenn M. Use of complex adaptive systems for modeling global change. Ecosystems 1998;1:457–63.

Levin SA. Concepts of scale at the local level. In: Logan JR, Field CB (Eds.), Scaling Physiologic Process: Leaf to Globe. New York, NY: Academic Press, 1993;7–19.

Centers for Disease Control. Introduction to the Syndemics Prevention Network. Atlanta, GA: CDC. July 16, 2003. Available at https://doi.org/www.cdc.gov/syndemics. Accessed on January 24, 2004.

Higginbotham N, Albrecht G, Connor L. Health Social Science: A Transdisciplinary and Complexity Perspective. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Prigogine I, Stengers I. Order Out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 1984.

Greenhalgh T. Change and complexity. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:514–15.

Peterson G. Political ecology and ecological resilience: An integration of human and ecological dynamics. Ecol Econ 2000;35:323–36.

Andrews G. The ecology of risk and the geography of intervention: From research to practice for the health and well-being of urban children. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 1985;75(3):370.

Kenkel NC, Irwin AJ. Fractal analysis of dispersal. Abstr Bot 1994;18:79–84.

Wallace R. A fractal model of HIV transmission on complex sociogeographic networks: Towards analysis of large data sets. Environ Plan A 1993;25:137–48.

Green LW, Richard L, Potvin L. Ecological foundations of health promotion. Am J Health Prom 1996;10:270–81.

Grzywacz J, Fuqua J. The social ecology of health: Leverage points and linkages. Behav Med 2000;26:101–15.

Duncan C, Jones K, Moon G. Health-related behaviour in context: A multilevel modelling approach. Soc Sci Med 1996;42(6):817–30.

Allen CR, Forys EA, Holling CS. Body mass patterns predict invasions and extinctions in transforming landscapes. Ecosystems 1999;2:114–21.

Enserink M. What mosquitos want: Secrets of host attraction. Science 2002;298:90–92.

Patil GP, Bishop J, Myers WL, Taillie C, Vraney R, Wardrop DH. Detection and delineation of critical areas using echelons and spatial scan statistics with synoptic cellular data. Available at https://doi.org/www.stat.psu.edu/~gpp/PDFfiles/TR2002-0501.pdf. Accessed on April 3, 2003.

Sallis JF, Owen N. Ecological models of health behaviour. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM (Eds.), Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2002;462–84.

Geomatics Canada. https://doi.org/www.nrcan.gc.ca/geocan/index_e.html. Accessed on March 21, 2003.

Gatrell AC, Dunn CE. Geographical information systems and spatial epidemiology: Modelling the possible association between cancer of the larynx and incineration in North-West England. In: De Lepper MJC, Scholten HJ, Stern RM (Eds.), The Added Value of Geographic Information Systems in Public and Environmental Health. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995;215–33.

MARA/ARMA (Mapping Malaria Risk in Africa). August 12, 2003. Available at https://doi.org/www.mara.org.za. Accessed on December 13, 2003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rainham, D.G.C. Ecological Complexity and West Nile Virus. Can J Public Health 96, 37–40 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404012

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404012